Do anger or outrage justify outrageous behaviour?

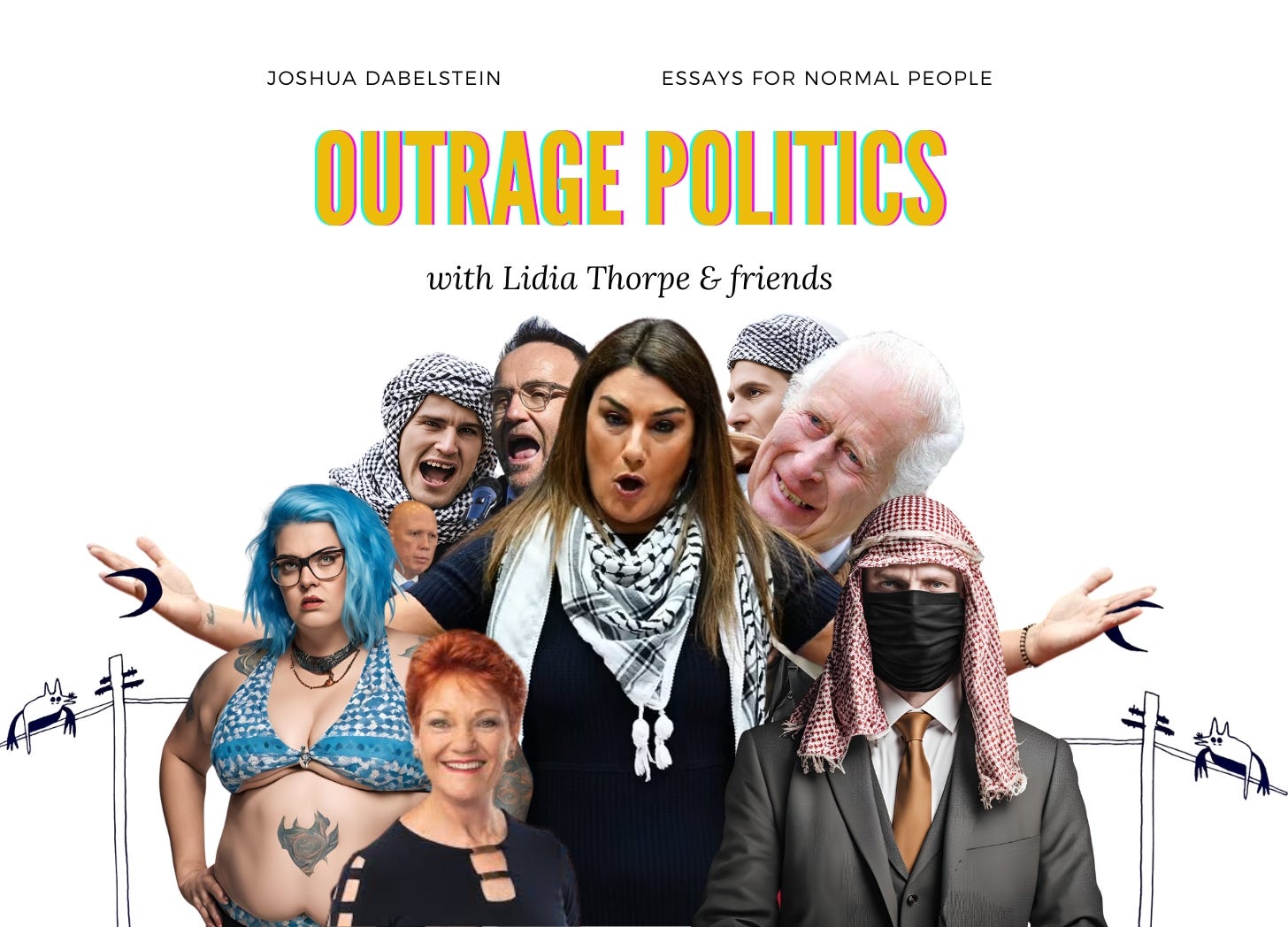

A quick look at Lidia Thorpe's not-so-secret weapon: the tantrum.

Anger is often referred to as a ‘secondary emotion’, arising from either physical or emotional pain. Sometimes anger manifests as a shield, which we hold in between ourselves and our own vulnerabilities. Other times we wield anger like a weapon, leering over people or situations we feel the need to control.

Anger often emerges as response to our inability to grapple with complexity, navigate difficulty, or reason with others. It obscures our ability to reflect upon our own inadequacies while directing us to tilt blame at others. While we do not choose to feel it, we can choose whether or not we should justify the repercussions it often incurs. Unchecked anger writes its own script: my anger is your fault.

At an individual level we usually attach shame and guilt to expressions of anger in its aftermath. Anger denotes a loss of control, a falling from grace, and a disturbing of one’s environment in a way that may harm others—sometimes by design.

Anger management classes abound, as do apology letters and promises to ‘work on it’ in between outbursts. Therapists cash in on anger’s ramifications in both personal and professional settings, and self-help gurus sell a plethora of snake-oils designed to assuage this most humiliating and destructive affect. Anger keeps courts full, relationships dangerous, and history repeating. Men are more comfortable expressing anger than sadness, and I truly believe that this bastardisation of our faculties is represented in Australia’s femicide statistics.

Despite all this, anger is not always something that we regard as a shortcoming. For those in public advocacy roles—be they as activists or politicians—anger can easily be misunderstood as passion or righteousness.

An advocate’s anger might, to many frustrated citizens, denote their passion, their outrage, or their commitment to integrity. At face value, the advocate’s anger looks like a valid or important response to unfairness, and by extension expresses the advocate’s commitment to change.

We are animals, after all, programmed to cower to, assuage, and take very seriously the mightiest roar, the toughest bite, or the loudest chest-thump. Perhaps anger and outrage are the 2024 homo sapiens’ response to the wolf’s raised hackles. Perhaps aggression has as important a run of the animal kingdom as it does our homes, parliaments, and workplaces.

But should it?

Despite this potential (and albeit flimsy) explanation for why we might still revere the angriest mammal in the room, I see no practical justification for it. I am not a bear or a kangaroo or a moose, and I will not impart serious attention to anyone just because they lack the ability to check themselves.

I say all this having given Lidia Thorpe the benefit of the doubt. It would be impolite to suggest that she is merely feigning outrage to manipulate people into thinking that she is both very passionate and very hard-working. It would be even more impolite to suggest that these tantrums aren’t designed to produce any kind of policy or social progress and are instead hollow and damaging publicity stunts.

In James Massola’s piece for the SMH, ‘Appetite for disruption: We’ve got to talk about Lidia Thorpe’, the author cites Monash University emeritus professor of politics Paul Strangio:

“It brings to mind the 1982 judgment of former High Court Justice Lionel Murphy when, in relation to an Indigenous leader, Percy Neal, Murphy, paraphrasing Oscar Wilde, declared ‘Mr Neal is entitled to be an agitator’.

“While her behaviour undoubtedly offends many, we may well ask if it’s reasonable to expect Indigenous Australians to be forever meek, polite and forbearing.”

While I understand Massola’s decision to include this, I just can’t bring myself to accept that Thorpe’s status as an indigenous female makes her antics in Parliament house any less outrageous. The idea that we must settle for an identity-politics-based two-tier set of standards for senatorial decorum feels racist and sexist.

And for the racists and the sexists out there arguing against Thorpe’s suspension—all those who deem aboriginal woman less capable of meeting general senatorial standards of conduct—might I ask: what of the practicalities of a multi-tiered code of conduct? Will this system be grandfathered out, or is the plan to allow some senators to behave differently to others ad infinitum?

I observe Senator Lidia Thorpe as a senator, nothing more, and nothing less. A senator who is sticking up her middle finger in parliament house, to name but one of many angry outbursts.

It is incumbent upon the electorate to understand how and why our advocates’ outrage might be obscuring the paths to progress that they, at face value, might profess to be clearing.

By mistaking an advocate’s anger as an indication of their commitment to a cause, we entrust those championing our interests with roles that they are ill-equipped to perform.

While anger expressed at protests or rallies may convey an important response to public policy or injustice, it is important to remember that this is an emotional response and does not in and of itself enact change.

This is not an argument against our right to get angry, especially when so many of us have so much to be angry about. But matters of public policy and injustice, just like a confrontation between two individuals, demand practical responses and pragmatic advocacy.

Do not mistake Lidia Thorpe’s angry outbursts for integrity, or evidence of her capacity (or even willingness) to use her position as a senator to help build a better Australia for all. Whether her outbursts are stunts, or actual expressions of anger, they only help to sew division, create confusion, and prevent her colleagues from getting anything done.

————————————

View abridged version here.

Excellent

Thank you